What, another top ten list?! I know, nobody wants this, and with the annual glut of top tens, why should they? But as with my list of the best movies of the decade one year ago, I was motivated by the thought (admittedly, a slightly arrogant one) that I could come up with a better list than most professional reviewers, who all seem to be shilling for a handful of well-promoted Oscar contenders (as usual), while lamenting what a bad year it was for the movies--which is only true if you don't look too far beyond what's showing at the multiplex. The usual rule is that only movies eligible for Academy Award consideration get included on these lists. But since I have nothing to do with that rigged horse race, I've broadened the scope of my list to include films that I saw at the Atlantic Film Festival or downloaded from the internet, but which haven't been released commercially in the US, as well as some slightly older ones that I belatedly caught up with in Montreal and on video.

1 Vincere (Marco Bellocchio) Giovanna Mezzogiorno gives the performance of the year in this wildly audacious biopic of Ida Dalser, who may have been the first wife of Benito Mussolini (played as a charismatic young socialist by Filippo Timi). When the latter switched from socialism to fascism and married Rachele Guidi, his relationship with Dalser (and their young son, Benito Albino) proved to be such an embarrassment that he had Dalser locked up in a mental hospital, and placed Benito Albino in an orphanage. In Bellocchio's hands, this shameful chapter in Italian history is given a mythic grandeur and operatic intensity. Boldly melodramatic and shamelessly manipulative, this is a political movie that can break your heart.

2 Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) Joe's best film yet is a rapturously beautiful magic realist fable about a man dying of kidney failure in a Thai farmhouse, where he's visited by the ghost of his dead wife, and his son who was transformed into a monkey with red eyes that glow in the dark. A visionary work encompassing the past, present, and future, the mythic and the everyday, the film also boasts the most impressive nighttime photography I've ever seen. (The cinematography is so dark that I seriously doubt the movie will work on video.) I've only seen it once, but it already feels like a classic.

3 The Headless Woman (Lucrecia Martel) The most audacious feature yet by the singularly talented Argentine filmmaker is a kind of reverse-amnesia movie about false memories, in which a middle-class dentist (María Onetto) comes to believe that she ran over a Gaucho boy with her car--not that anybody seems to care. Like Martel's earlier La Ciénaga (2001) and The Holy Girl (2004), this is a film that benefits from a second viewing as her method of withholding exposition and her off-centre framings often make the viewer feel as disoriented as the heroine. Given that most commercial features are meant to be understood and consumed immediately (time is money, as they say), Martel's insistence on making films that require close attention and multiple viewings is almost a political act.

4 Un prophète (Jacques Audiard) Following a French-Arabic inmate (Tahar Rahim) from his arrival in prison as a teenager through his ascension to underworld kingpin, this ambitious crime saga has a novelistic scope that's inspired some reviewers to liken it to The Godfather (1972). But I like it even better than that film, in part because Audiard doesn't romanticize crime through his style. The drab institutional settings and unlikeable characters of this movie are a world away from the classy trimmings of Coppola's film, in which the mob is run by wise patriarchs who dress in smart clothes and live by a moral code. It's a bit of a sausage-fest, but I suppose that comes with the territory.

5 The Ghost Writer (Roman Polanski) The hero of this atmospheric thriller, based on a 2007 novel by Robert Harris (unread by me), is a nameless ghost writer (Ewan McGregor) hired to work on the memoirs of a former British prime minister (Pierce Brosnan) under investigation for war crimes. The latter is plainly a stand-in for Tony Blair, and the running gag about the writer having to go through constant security checks speaks to the times we live in. But above all, this is just a beautifully crafted movie. Paring down each shot and line of dialogue to only what's essential, Polanski is such a supremely confident storyteller that he makes it look effortless.

6 Greenberg (Noah Baumbach) A romantic comedy that you see alone, starring Ben Stiller in the title role as an abusive middle-aged crank, who agrees to take care of his brother's dog while he's away; Greta Gerwig as the brother's slatternly personal assistant, who has to take care of Greenberg; and Rhys Ifans as his best friend, a recovering alcoholic who still nurses a grudge against Greenberg for the breakup of their band twenty years ago. This is a quiet, sad, sometimes funny movie about three seriously screwed up people, and I loved every minute of it. I wasn't a fan of Baumbach's early work, but with Margot at the Wedding (2007) and now this film, he's emerged as one of the finest directors working anywhere, and one of the edgiest.

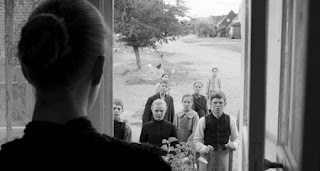

7 The White Ribbon: A German Children's Story (Michael Haneke) Set in a preindustrial German village on the eve of the first world war, this rare period film by the director of The Seventh Continent (1989) and Code inconnu (2000) is a chilling portrait of a repressive and puritanical society. Narrated by the local school teacher from a distance of several decades, the film centres on a series of unexplained crimes in the village, and Haneke uses the gaps in the narrator's knowledge to justify the gaps in the story, so don't go in expecting a conventional denouement. Characteristically spare and masterful as storytelling, this strikes me as Haneke's leanest and meanest effort since La Pianiste (2001).

8 Film socialisme (Jean-Luc Godard) I suspect that this three-part semi-narrative by my favorite filmmaker will look even better in a few years, once I've had time to better sort through it. Godard's films invariably grow in stature over time (unlike most Oscar winners), so the fact that I couldn't always follow what was happening in the story is more of a positive than a negative. In the meantime, what I can say for certain is that the film's opening segment (set on a cruise ship sailing around the Mediterranean) is a dizzying assault on the senses, boasting the worst sound I've ever heard in a commercial feature. And what follows, though more expected, is consistently singular and beautiful.

9 Carlos (Olivier Assayas) Even in the severely abridged 140 minute version that I saw at the Atlantic Film Festival (cut down from a five hour miniseries), this epic biopic of the international terrorist and media superstar, Carlos the Jackal (Édgar Ramírez), is still rather a full meal, covering a period of twenty years during which Carlos' waning influence is mirrored by the effects of aging on his body. Despite the film's anti-psychological docudrama style, which seems to be merely reporting the facts of the case, Assayas freely invents wherever there are gaps in the public record--as in the film's lengthy account of the OPEC Hostage Crisis in 1975, which as a piece of filmmaking is as suspenseful as anything I saw this year. I can't wait to see the longer cut.

10 Night Mayor (Guy Maddin) Western Canada's greatest auteur commemorates the 60th anniversary of the NFB (and the country's policy of multiculturalism) with this allegorical avant-garde short about a Bosnian tuba player's experiences in the new world. Only fourteen minutes long, this is the shortest item on my list, but every second of it is densely packed. The flickering, rapidly edited multiple exposures and layered soundtrack demand multiple viewings, making this Maddin's best short film since My Dad Is 100 Years Old (2005).

Some other movies that I liked:

Les Amours imaginaires (Xavier Dolan) Eastern Canada's youngest auteur follows up the success of J'ai tué ma mère (2009) with this funny and stylish homage to Godard and Wong Kar-wai, in which glam Francophone hipsters walk around Montreal in slow motion to an Italian language cover of Nancy Sinatra's "Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)."

Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl (Manoel de Oliveira) Adapted from a short story by the 19th century Portuguese novelist José Maria Eça de Queirós (which I haven't read) but set in the present, this singular and masterful film by the world's oldest living filmmaker is enhanced, rather than diminished, by its remoteness from the present. It's indicative of the film's endearingly old fashioned quality that when the hero (Ricardo Trêpa) moves to kiss the title character (Catarina Wallenstein), the film cuts away to their feet.

Exit Through the Gift Shop (Banksy) A multifaceted and very funny documentary about Thierry Guetta, who's better at playing the artist than he is at actually making art. In the late '90s, Guetta began documenting the work of several prominent street artists, including Banksy who inspired Guetta to become an artist himself. The film consists largely of Guetta's own footage, which Banksy has edited to make his former friend (and the art world in general) look as ridiculous as possible.

Les Herbes folles (Alain Resnais) Adapted from Christian Gailly's 1996 novel L'Incident (unread by me), this mind-boggling tale of l'amour fou is enhanced, rather than diminished, by its remoteness from sanity. It's indicative of how freakin' crazy this movie is that when the two leads (Sabine Azéma and André Dussollier) finally embrace, the 20th Century Fox fanfare rises on the soundtrack, and the word "Fin" blinks on the screen, even though the movie isn't over.

Hereafter (Clint Eastwood) I'm a devout atheist, but even I couldn't help being moved by this sombre afterlife drama which tells three separate stories, each set in a different country. The film opens with a harrowing recreation of the 2004 Asian Tsunami, but the most moving scenes are often the quietest--particularly those involving a solitary young boy from London's East End (Frankie and George McLaren) whose twin brother dies in a car accident, and between a former psychic who just wants a normal life (Matt Damon) and the nice girl he meets in his cooking class (Bryce Dallas Howard, playing Mary Jane to Damon's Spider-Man).

Home (Ursula Meier) Along with Exit Through the Gift Shop and I Love You Phillip Morris, the best first film I saw this year was this creepy French nuclear family freak out, which at times recalls Todd Haynes' Safe (1995). Meier shot the film on a remote stretch of highway in Bulgaria, and the landscape (which is as desolate as the surface of the moon) feels concrete and mythic at the same time.

I Love You Phillip Morris (Glenn Ficarra and John Requa) The first film by the writers of Bad Santa (2003) is a bold and uncompromising biopic of Steven Jay Russell (Jim Carrey), a Texas con man whose multiple escapes from prison were such an embarrassment to then-Governor George W. Bush that he was given a 144-year sentence, despite being a nonviolent offender. I'm generally a fan of Carrey's (I even liked Yes Man [2008]), but this movie is especially intriguing for the way it undermines easy identification with him at every turn.

Milyang (Secret Sunshine) (Lee Chang-dong) I'm cheating a bit by including this Cassavetes-like freak out by the wild man of South Korean cinema, since I actually first saw it a couple of years ago. However, I've decided to put it on my list anyway as it's only now getting a limited US release.

My Dear Enemy (Lee Yoon-ki) Perhaps the most overtly populist item on my list, this is an old fashioned crowd-pleaser about people sticking together in tough financial times. The two leads, Jeon Do-yeon (who was also in Milyang) and Ha Jung-woo, are both delightful, and although this is essentially a light comedy, the film nevertheless gets into some interesting ethical grey areas involving friendships and money.

You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (Woody Allen) Allen's best film since Match Point (2005) is a mostly lighthearted network narrative set in London about a group of people who are all in denial about various things. The movie has an unexpected ending that makes you look at the entire film in a different light, so that what seems to be a story about romance turns out to be about something else entirely. Allen is like a magician diverting us with misdirection while hiding his tricks in plain sight.

Friday, December 17, 2010

Hindsight Is 2010 (My Favorite Movies of the Year)

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Senior Class: Woody Allen and Clint Eastwood

According to a recent news item in The Telegraph, researchers at the University of Montreal set out to compare the views of men in their twenties who had never seen pornography with those of regular users. The problem was that they couldn't find anyone who had never seen porn. On average, the study found that single men in their twenties spend two hours a week watching porn, while men in relationships spend thirty-four minutes a week looking at it, and with no negative consequences.

I don't imagine that Woody Allen, who turns seventy-five in December, spends much (if any) time on the internet, where the study finds that ninety percent of wanking occurs. But watching his new film You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010) again after reading about the study, it seemed that Allen's insights into the male psyche shed some light on why men are such compulsive masturbators.

A multi-protagonist comedy-drama set in London, the film's subject is the different ways people find of not dealing with certain harsh realities. The movie opens with Helena (Gemma Jones), a visibly frazzled middle-aged woman, going to see a fortune teller, Cristal (Pauline Collins), who tells her what she wants to hear and charges her for the service. We learn that Helena's longtime husband, Alfie (Anthony Hopkins), has left her because he's going through a midlife crisis and wants to have a son. After an unsuccessful attempt at the dating scene, Alfie calls in a professional, Charmaine (Lucy Punch), who tells him what he wants to hear and charges him for the service. Alfie soon finds himself hopelessly in love with Charmaine and proposes marriage.

Alfie and Helena's grown daughter, Sally (Naomi Watts), also wants to have a child, but she needs to find a job because her American husband, Roy (Josh Brolin), isn't working at the moment. Early in the film, she interviews for a position at a posh art gallery run by Greg (Antonio Banderas), whom she quickly develops a crush on. Meanwhile, Roy, a former medical student turned novelist, is anxiously waiting to hear from his publisher about a manuscript he submitted. If Roy had a Wi-Fi connection, he might distract himself by spending thirty-four minutes a week on the internet, but instead, he begins spying on Dia (Frieda Pinto), a professional musician who lives in the apartment across the street.

Neither Sally nor Roy believes in fortune tellers, but Sally goes along with Helena's fantasy as long as it makes her happy. Conversely, although Sally disapproves of Alfie's marriage to Charmaine, Roy thinks it might be good for him. On their first date, Charmaine tells Alfie that she's primarily an actress, leading Sally to ask, "An actress in what?" This is the movie's most explicit reference to pornography, yet Allen (perhaps without even realizing it) seems to be working out some of the implications of pornographic films and literature. As Kurt Vonnegut put it in his novel God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965), what pornographic books offer the reader are "fantasies of an impossibly hospitable world."

Here, the characters are all nursing their own hopeful delusions: Helena that Cristal can predict the future; Alfie that he's still a young man; Sally that Greg shares her feelings; Roy that he's a novelist. Perhaps Alfie is a little more deluded than the rest, and accordingly, his scenes with Charmaine are the film's most broadly comedic (even if Hopkins' performance is as understated as his work in James Ivory's The Remains of the Day [1993]). After all, several of Cristal's predictions do come to pass; Greg does say that he's having trouble at home, and Sally is an attractive woman; and we're told that Roy's first novel did show some promise. And if the delusion makes you happy, then why not? It's only when the characters' delusions start crashing against reality that the problems start. So naturally, the only character who finds some measure of contentment at the end of the film is Helena, who finds some one to share her delusions with.

The film is just brilliantly written. A lot of movies in recent years have had several intersecting story lines, but often with the characters isolated on separate continents. Here, where the characters all know each other, Allen is able to update us on the status of several different plot lines within the same scene. A key sequence here, which comes deep into the film, begins with Sally coming home in a state after learning that Greg is already having an affair with some one else. She finds Roy on the couch sipping a beer, and when she asks him if he's heard yet, he has to ask her, "Heard about what?" such is his present state of contentment with Dia that any anxiety he felt about his new book now seems like a distant memory.

As Sally moves about the room looking for an aspirin, she talks about how dissatisfied she is working for Greg (a complete reversal from her feeling earlier) and how she needs to start her own gallery (announcing a new goal for herself). Greg then gets a call from his publisher, informing him that his book's been rejected. And while he's talking on the phone, Helena shows up at the door to announce to Sally that she's had a breakthrough with Cristal, and now believes that she's lived before. Cristal had earlier predicted that Roy's book wouldn't be published because the timing wasn't right, and now Helena tries to reassure him by saying that maybe he'll be a writer in another life--which is manifestly not what Roy wants to hear.

As a rule, Allen's British films tend to be superior in craftsmanship to his recent American movies, even when the material isn't up to par, as in Cassandra's Dream (2007)--as opposed to Melinda and Melinda (2004) and Whatever Works (2009), which felt rather slapdash. (That said, I still liked the latter quite a bit.) Here, the cream-coloured production design by Jim Clay (who also worked on Match Point [2005]), and the light, airy cinematography by Vilmos Zsigmond set just the right mood for the picture. Also, this is one of Allen's most inventively staged films with the actors in near-constant motion, often in extremely long takes with a mobile camera. But because Allen's technique is firmly "in the service of his material," as they say, you might not notice how masterfully constructed the film is unless you're paying attention. Nothing here happens by chance (seeing the film a second time, I realized just how obsessively colour-coordinated the film's palate is in every single shot), yet because Allen is so completely in control of the medium, it feels almost effortless. This is Allen at the top of his form.

I've seen Clint Eastwood's Hereafter (2010) twice, and I had a different response to it each time. The first time I saw the film, it just raped my tear ducts. But seeing it again, it put me in a more thoughtful mood--or maybe "thoughtful" isn't the right word, since I wasn't thinking about anything. Maybe the first time I saw the film I was responding more to the story, while the second time I was responding to the mood of the film.

This control of tone hasn't always been Eastwood's strong suit. Even in Changeling (2008), where he had a pretty good script by Michael Straczynski, the muted colour scheme and sombre, high contrast lighting seemed at odds with the cheerfully lurid story, and the performances were all over the map, from Angelina Jolie's aggressive Oscar-baiting as a saint-like single mom to Amy Ryan's streetwise prostitute to Jason Butler Harner, who attempts to outdo Peter Lorre in M (1931) for nervous excitability. Also, not to hate on Angelina Jolie just for being Angelina Jolie, but her lips are so big and so red, and everything else is so monochromatic and blue-grey, that they become the focal point of every single shot in which she appears. And you'll notice that whenever Jolie has a big, emotional close-up in the film, she always covers her mouth.

In this film, however, everything comes together in perfect harmony: The script, performances, cinematography, production design, sound mix, and score all work together to create a mood that's exquisitely subdued; this is one of the quietest American studio films of recent memory. Written by Peter Morgan, the film is a multi-protagonist drama which tells three separate stories, each one set in a different country, and its best scenes are often the saddest. One thread, set in San Francisco, involves a former psychic, George (Matt Damon), whose powers of perception make it difficult for him to have any kind of personal life. In an attempt to meet some one, George signs up for night classes in Italian cooking, where he meets Melanie (Bryce Dallas Howard), who's new in town and is looking to make new friends. The chemistry between these two provides some of the film's rare lighter moments, but when they go back to George's apartment and Melanie discovers his hidden talent, things take a sudden turn for the serious. Another story, set in London's East End, centres on twin boys, Jason and Marcus (Frankie and George McLaren), whose mum, Jackie (Lyndsey Marshal), is a junkie but not an unaffectionate one. When Jason is killed in a car accident, Marcus (the more introverted of the two) is placed in a foster home while Jackie gets herself sorted. Like Nicholas Ray, Eastwood seems drawn to stories about loners from broken homes.

The third story line is about a French journalist, Marie (Cécile de France), who almost dies in the 2004 Asian Tsunami. The sequence representing this event, though obviously done on computers, is nonetheless awesome because it gives you a sense of what it's like to be swept up in a fast-moving current which is less dangerous in itself than all the objects moving around in it (such as shopping carts and cars) that you can get caught on or crushed by. After getting whacked on the head, Marie sees a white light and lots of backlit figures which are supposed to represent the afterlife. (Just as the movie makes a point of not telling us which country she's in during the tsunami, the film's version of the afterlife is entirely nonsectarian. And later, there are broad satiric swipes at both Islamic and Christian whack jobs for good measure.) Upon returning to Paris, Marie finds that her heart just isn't in her work anymore, and her producer-boyfriend, Didier (Thierry Neuvic), suggests that she take some time off to write a book. But when she decides to write about her experience, she finds that no one wants to listen. According to the film, there is really is an afterlife and science can prove it, but the evidence has been suppressed by left-wing atheists in the media like Didier. In Switzerland, Marie meets a formerly skeptical doctor (Marthe Keller) who says that what convinced of an afterlife was that so many people reported seeing the same things, which is also true of UFO sightings.

Each story has a slightly different look, and in each one, the film seems to be referencing a particular genre associated with the different countries. The American story is like a superhero movie without any action scenes, complete with an origin myth (in this case, a childhood surgery gone wrong, rather than a mutant spider bite), and a hero who has to chose between using his powers to help total strangers and having a relationship with a nice girl. (George even says at one point, "It's not a gift, it's a curse!") The scenes in Britain are played for kitchen sink realism, and one early sequence is shot atypically with a handheld camera. And the Parisian story line, which takes place largely in steel-and-glass skyscrapers and fancy restaurants (reflecting the fact that the characters here are more affluent), is a politically tinged relationship drama. (Marie's first interview upon returning to her regular job as a news anchor is with a CEO whose company exploits third world labor, and before writing about her experience during the tsunami, she pitches her publisher a book about François Mitterrand.) The décor, particularly in Marie's apartment, tends toward bright, clinical whites, while the scenes in San Francisco and London emphasize blue and brown, respectively.

The film is not without its rough spots. Inevitably, the three stories converge at a book fair in London, where Marie is promoting her book. Marcus' foster parents take him there in order to meet their previous foster child, who has a job as a security guard. But Marcus, being the withdrawn kid that he is, asks if he can wander off on his lonesome for a while. George has just bought a copy of Marie's book when Marcus recognizes him from the picture on his website, which hasn't been taken down. But what exactly is George doing in London? You see, George's favorite author is Charles Dickens (more than once in the film, we see George listening to his works on tape), so when he needs to get away for a while, George decides on England. The first thing he does there is to visit Dickens' home, and it's there that he sees a poster advertising a reading of Little Dorrit (1855-57) at the book fair. Obviously all stories depend on coincidence, but as a character trait, George's enthusiasm for Dickens seems rather arbitrary. The cooking lessons make sense, because as the teacher (Steve Schirripa) says at one point, cooking involves all the senses (to add an acoustic element and set a romantic mood, the teacher plays Italian opera during class)--in other words, cooking is life. But why Dickens, and not any other British novelist, except of course that Dickens is by far the most famous? When Melanie notices a sketch of Dickens in George's apartment, he says to her, "People go on and on about Shakespeare, but Dickens is just as great" (never-mind that Shakespeare wrote plays and sonnets in the Elizabethan era, while Dickens wrote serialized novels in the Victorian era), which is the closest he comes to explaining his affinity for the author of Bleak House (1852-53) and Great Expectations (1860-61).

Of course, that's pretty minor next to the lapses in storytelling in some of Eastwood's other pictures, such as Million Dollar Baby (2004), where Paul Haggis' (Oscar-winning) script suddenly introduces a glowering German villainess to paralyze the heroine for no reason at all, and then has her disappear from the film entirely. But here, even when the screenplay stumbles slightly, the look and sound of the movie (when there is music, it's non-obtrusive) and the performances are so much of a piece with one another that the execution carries the viewer over any tiny flaws in the conception. And despite the heavy tone (the film's cinematographer isn't named Tom Stern for nothing), Eastwood shows a lighter touch than in any other film of his I've seen. In part I think that's because Morgan's script doesn't portray any of the characters as a pure villain; even when George gets laid off from his warehouse job, he's not mad at the foreman, who's just protecting the guys who have families. But also, notice how in the scene where Melanie first walks into the cooking class, an old man standing next to George straightens his collar a little bit. The old man is in the background of the shot and out of focus, but by placing the teacher (the apparent focal point of the shot) to the left side of the screen, and the old man in the direct centre of the frame, Eastwood subtly shifts the emphasis away from the teacher. And when you compare this nice little comic touch with some of the comic relief characters in Eastwood's other films, like a dumb blonde in the otherwise brilliant White Hunter, Black Heart (1990) who's trying to sell a screenplay about a dog, you almost can't believe it's the same director. This is Eastwood at the top of his form.

Saturday, October 9, 2010

How to Build a Better Filmgoer: Some Brief Thoughts on "Made in USA" and the Total Revolution of Society

When most people go to the movies, they aren't looking for something new but something familiar, like a petulant child who insists on being read the same bedtime story every single night. At the broadest level, a commercial feature is supposed to tell a story in three acts with a turning point (David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson use the more precise terminology of setups, complicating actions, developments, and climaxes), and the rules of continuity editing, which were established in the 1910s, give viewers the feeling of being an invisible observer. More locally, mainstream films are classified by genre, although the rules governing genres tend to be more flexible than those around dramatic structure and editing. One intriguing example of genre-bending that was on TV a few days ago is Michel Gondry's Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), which combines two genres not usually associated with each-other: the romantic comedy and science fiction. However, as unusual as the film is by mainstream standards, it still adheres to certain conventions which make it accessible to a wide audience. On the other hand, screening Film Socialisme (2010) for a mainstream audience (including most professional reviewers) makes as much as sense as reading Gravity's Rainbow (1973) to a four year old. The question is: How you do make better audiences?

Made in USA (1966) came towards the end of Jean-Luc Godard's most commercial period, and it has both a glamourous star (Anna Karina, in her next-to-last film with Godard) and something like a conventional revenge plot, in which the heroine, Paula Nelson (Karina), has to find and kill the person who murdered her fiancé. (As with Godard's earlier Bande à part [1964], the story is loosely derived from a pulp American novel.) However, the first thing one notices about the film in relation to most commercial movies is that it's abnormally talky, and (characteristically for Godard) the dialogue only intermittently advances the plot. (In one sequence in a bar, a working man spouts nonsense sentences, such as "The window looks out of the girl's eyes," while Marianne Faithful sings "As Tears Go By" a cappella.) The constant digressions and jokey tone prevent the viewer from getting very involved in the silly plot, so even though I've seen the film twice, I couldn't tell you what happened in any detail--not that it really matters anyway. So what actually interests Godard? The narration tells us that this is a political film, and the dialogue is peppered with allusions to current events (local elections, the Mehdi Ben Barka case), but Jonathan Rosenbaum's description of Jim Jarmusch's The Limits of Control (2009) as "filmmaking for its own sake" seems closer to the mark.

In Made in USA, local texture is everything, and the plot is simply a means of getting from one moment to the next. At one point, Godard lavishes as much time on a sequence showing Paula/Karina walking through a women's gym as he does on the perfunctory exchange between her and a doctor that supposedly justifies it. (When the latter insists that Paula's fiancé died of natural causes, she quips that, even in Auschwitz and Treblinka, there were people who died of heart failure.) Some other memorable bits: Paula playing "hot and cold" with a gangster (Jean-Pierre Léaud) in an abandoned garage; Paula beating an old man unconscious with a high heeled shoe, scored to a sudden burst of Beethoven; Paula in a plastic surgeon's office unwrapping the bloody bandages over a skeleton with bulging eyes resembling a Matt Groening character. To be sure, this yields diminishing returns as the film goes on (at eighty minutes, it's not a moment too short). However, I liked the movie (and The Limits of Control) better on second viewing, which is almost always the case with Godard. More than any filmmaker I can think of, his work requires a certain degree of adjustment on the part of the viewer. So whereas on first viewing I was still in the same frame of mind as I would be while watching any normal film, the second time around, I had a better idea of what I was in for.

Reviewing Film Socialisme from Cannes (or more accurately, reviewing its director and his fans), Roger Ebert described Godard's defenders as his "acolytes," and speaking as a fanatical Godardian myself, the question for me is how to convert the unbelievers? Rather than attempting to radicalize cinematic consciousness one person at a time, I think the simplest thing would be total revolution. After all, since commercial cinema is a product of the capitalist system, in order to reform it, we'd have to change society as well. The first thing we'd have to change is to make it illegal to make a profit off of cinema. So instead of major studios looking to maximize their profits, programming would be the responsibility of local curators--people with some knowledge of film history whose goal would be to educate the tastes of filmgoers. To this end, they would screen both classics and fresh discoveries from around the globe. The curator would be able to get feedback from viewers on the kinds of films they'd like to see, and independent filmmakers would have easier access to a local audience, fostering atomized, heterogeneous film cultures. So instead of a top-down system, in which the same blockbuster opens on three thousand screens simultaneously preceded by a massive ad campaign, we'd have a more democratic system that people could actively participate in rather than just passively taking it up the ass.

Wednesday, October 6, 2010

The Sound and the Fury: Some First Impressions of 'Film Socialisme'

While it's too early on the basis of a single viewing to say whether or not Film Socialisme (2010) is a masterpiece, if nothing else, Jean-Luc Godard's latest mind-boggling contraption makes every other new commercial feature look horribly antiquated and square by comparison, like something you'd find collecting dust in your grandma's attic. Let's face it: Compared with Godard, most other filmmakers just aren't working very hard.

The opening scenes in particular, which take place on a cruise ship sailing around the Mediterranean, find the octogenarian master at his most assaultive and perverse. And I mean that as a compliment. The first thing one notices about the movie is that it has the worst audio you've ever heard in a commercial film. Godard shoots in windy conditions evidently without a wind sock. In some scenes, the ambient audio abruptly cuts out between lines of dialogue. And at times, there's a distinct hissing noise on the soundtrack--exactly the sort of audio glitch you'd expect to find in a video posted on YouTube but not a professional feature film. Audiences are pretty forgiving of crappy cinematography, but sound is another matter entirely; even the drabbest of drably-shot of American indies coming out of the South by Southwest scene will have a clean, professional sound mix. Here, it's as if the most sophisticated filmmaker ever to work in the medium, and one of the most innovative when it comes to sound, were trying to convince us that he's never used a microphone before in his life.

After this opening barrage, however, the film seems to back down somewhat. The second part of the film, set in a family-run garage in rural France (or is it Switzerland?), has good quality sound and is even slightly easier to follow as storytelling. Of course, compared to the majority of commercial movies, even this part of the film is radically unorthodox: Godard characteristically separates dialogue from image, and withholds exposition about the characters. But still, this isn't anything that Godard hasn't been doing for the last thirty years. Likewise, the film's final sequence is a typically beautiful, poetic, non-narrative video montage whose geographic itinerary neatly echoes that of the cruise ship in the movie's opening scenes: Egypt, Palestine, Odessa, Greece ("Hell As"), Naples, Barcelona. Godard gracefully weaves together documentary footage with clips from old movies (including, natch, the Odessa Steps sequence from Battleship Potemkin [1925]), and onscreen text and narration with a keen sense of juxtaposition and rhythm. Viewers who've made an effort to keep up with Godard's recent output will recognize some of the clips used here from his short masterpiece Dans le noir du temps (2002) and the "Inferno" sequence from Notre musique (2004). And if I'm not mistaken, he's used the same crashing piano theme before as well, although I can't recall where.

When the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May, it was shown with subtitles in "Navajo English." For instance, according to Michael Sicinski, the name Goldberg in the first part of the film was translated at one point as "gold mountain," which is obviously relevant given that the character in question is a Nazi war criminal who plundered gold from Spain during the civil war. Watching the film on my laptop, however, I had to settle for conventional English subtitles (which only translate the film's French dialogue and titles, and not any of the other languages spoken in the film). It's hard to say, alas, whether this puts me at an advantage or a disadvantage. In any event, I doubt that the subtitles I saw would change Todd McCarthy's mind about Godard being a member of "the ivory tower group" of filmmakers "whose audience really does consist of a private club with a rigorously limited membership." Now that the secret's out, I guess I might as well tell you that we don't actually meet in an ivory tower, but because of the recession, we've had to downgrade to a modest chateau in Switzerland, where we consider how many applicants we can reject each year for not being elite enough and still bring in enough money to keep the lights on.

Returning to the film, for McCarthy, "What we have here is a failure to communicate." My feeling is that people who talk about "getting" a film (including Pauline Kael, who famously never saw a film more than once on the basis that she "got" it the first time) really don't get it at all. McCarthy talks as if Godard only had one point to make, and that his job as a filmmaker is simply to get viewers across the finish line of understanding. (At which point, presumably, the movie ends and everyone can put on their coats and go home, having "gotten their money's worth," as the saying goes.) For one thing, Godard doesn't strike me as a very linear thinker. In this film, a young black woman says at one point, "You want to hear my opinion? AIDS is just an instrument to kill the black continent." To which her white companion replies, "Why is there light? Because there is darkness." Clearly the latter thought doesn't follow logically from the previous one, but by placing them side by side, Godard invites viewers to make an association. The same principle applies later on when Godard juxtaposes a shot from Battleship Potemkin of a crowd waving to the boat as it comes into port with a contemporary scene of two Ukrainian teenagers waving to a cruise ship as it sets sail. To make a connection between the two sentences or the two shots requires a degree of inference-making that goes beyond the letter of the text, but has nothing to do with getting (or not getting) a particular point.

To be fair to McCarthy and Roger Ebert, who also missed the cruise ship on this one, we should take into account that their job consists largely of reviewing films that are designed to be understood and consumed in a single go. The only American commercial film I can think of that even comes close to what Godard is doing here in terms of audio and montage is Terrence Malick's The Thin Red Line (1998), which split reviewers when it first came out but today feels like a canonical classic (especially now that Criterion's released an expensive Blu Ray edition). That's not to say that Godard's film will become an accepted classic in ten or twelve years (unlike Malick's film, it doesn't have studio backing or any stars, so it won't get a wide release), but I can't think of any recent commercial film that I'm as eager to watch again--maybe this time with those crazy Navajo subtitles so I can see what I'm missing.

Monday, September 27, 2010

AFF #5: When the Fact Becomes Legend

Even in the severely abridged version that was shown at the Atlantic Film Festival (cut down to a 140 minute feature from a five and a half hour miniseries), Olivier Assayas' Carlos (2010) is still rather a full meal: an engrossingly factual account of the career of international terrorist and media superstar Carlos the Jackal (Édgar Ramírez) spanning more than two decades. The film opens in 1973, when Carlos was ordered by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) to shoot Joseph Sieff, a Zionist businessman, in London in retaliation for the assassination of Mohamed Boudia by Mossad, and it ends in 1994 with Carlos' capture in Sudan by French authorities. However, as ambitious and as gripping as the film is, one can't shake the sense that Assayas is playing it straight here in relation to his even wilder films like demonlover (2002) and Boarding Gate (2007); aside from the rock music on the soundtrack, I don't think this is noticeably different from what the Paul Greengrass version would look like. Eschewing interiority, the film takes a radically objective approach to its subject, only hinting at Carlos' relationships with the various comely women who swim in and out of focus over the course of the movie, including his marriage to Magdalena Kopp (Nora von Waldstätten) of the Baader-Meinhof Gang. There are obvious affinities between this film and Steven Soderbergh's Che (2008), but Assayas' (at least in its abridged version) is much more confident as storytelling, moving with an ease and forward momentum that eluded Soderbergh, who tended to get bogged down in pointless minutia.

The obvious high point of the film is its detailed treatment of the OPEC Raid in 1975, in which members of the FPLP under Carlos' command stormed a meeting at OPEC headquarters in Vienna, taking over sixty hostages (among them eleven ministers from oil producing nations), and in the process, killing an Austrian policeman, an Iraqi OPEC employee, and a member of the Libyan delegation. (The movie opens with a title card explaining that there are still grey areas in Carlos' life, and that the film has to be taken as a work of fiction. And looking at the Wikipedia entry on him, the OPEC Raid appears to be one of them, with various conflicting accounts of what actually happened.) According to the film, the idea for the raid came from Saddam Hussein (some say it was Muammar al-Gaddafi), who wanted the FPLP to assassinate two of the hostages--the finance minister of Iran, Jamsid Amuzgar, and the oil minister of Saudi Arabia, Ahmed Zaki Yamani (Badih Abou Chakra)--in order to advance his own goals in the region (namely, war with Iran). In both the film and in life (at least, according to Yamani's Wikipedia page), Carlos informed Yamani during the hostage crisis of his intention to kill him and the Iranian minister, but in the end (spoiler alert!), he cut a deal with the Algerian government for the release of all the hostages, and was kicked out of the PFLP for not carrying out his orders.

If the film's energy diminishes in the second half (as is also the case with demonlover and Boarding Gate), perhaps that's by design. Or maybe Assayas just can't keep up this level of intensity, which is less a serious failing than an indication of how tight the early scenes are. After getting thrown out of the PFLP, Carlos started his own group, the Organization of Arab Armed Struggle, and formed contacts with the East German Stassi. However, when he and Kopp were expelled from Hungary in 1985, Carlos was only allowed into Syria on the condition that he not pull off any further terrorist attacks. By the end of the Cold War, Carlos had become completely irrelevant, and at one point in the film, he's told that the CIA now thinks of him as a "historical curiosity" (a line reminiscent of the description of Michael Madsen's character in Boarding Gate as a "perfect cliché of bygone times"). As Carlos becomes increasingly ineffectual and obese, the film begins to feel almost like a remake of Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull (1980); in both movies, the protagonist's sense of stature is intimately tied up with the physical condition of his body. Here, Carlos finds himself a lame duck terrorist, adrift in a world that's stopped paying attention to him. Che Guevara was killed and became a martyr, but fate was much crueler to Carlos, who's still alive, sitting a French prison, a forgotten man.

I rather dread having to write about Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman's Howl (2010) simply because I don't know the first thing about poetry. The film opens in 1955 with Allen Ginsberg (James Franco, looking like the offspring of Matt Dillon and Lee Evans' characters in There's Something About Mary [1998]) giving the first public reading of his poem "Howl" to an appreciative boho audience in a San Francisco café. Over the course of the film, we hear most or all of the poem, which is illustrated at various points by animated sequences in which we see, for instance, swarms of ephemeral white banshees flying sperm-like above city skyscrapers to represent Ginsberg's "Angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night." Or at least I think that's what they're supposed to represent. Ironically, one definition we're given of poetry in the film is that it can't be explained, or else it would be prose. How are you supposed to illustrate a line like, "Who ate fire in paint hotels or drank turpentine in Paradise Alley, death, or purgatoried their torsos night after night / with dreams, with drugs, with waking nightmares, alcohol and cock and endless balls," and why would you want to? I'm asking.

The film also makes use of two related texts, both from 1957: An audio recording of Ginsberg talking about his early life and creative process, and the transcript of the obscenity trial that resulted from the poem's publication, both of which are reenacted for the camera using Hollywood actors. Mercifully, the film largely refrains from preaching the importance of free speech to a free society blah blah blah. Instead, the trial seems to have focused primarily on the question of whether "Howl" has any artistic merit, which required the lawyers for the defense (John Hamm) and the prosecution (David Straitharn), and their expert witnesses, all of them English professors, including Jeff Daniels in a virtual reprise of his role from The Squid and the Whale (2005)--alas, without the beard--to try to grapple with the meaning of the text in the author's absence (technically, Ginsberg wasn't on trial for writing "Howl," but his publisher for printing it). In other words, the film tries to make some sense of the poem for philistines like me who wouldn't know what to do with Ginsberg's poetry if they did read it. And in my uneducated opinion at least, that's a lot more interesting and useful than the usual biopic claptrap.

William D. Magillvray's Man of a Thousand Songs (2010) was the winner of the audience award at the Atlantic Film Festival, but I have two reasons for being dubious of this. One, it's a local production (well, Newfoundland. Close enough), so most of the people who went to see the film either worked on it or know some one who did, so of course they're going to mark "outstanding" on their ballots. Secondly, it's a music documentary, so if you like the subject, you're probably going to like the movie (unless, that is, you're a curmudgeon like me). All week long I've been trying to understand why people liked Johann Sfar's dreadful Gainsbourg (vie héroïque) (2010), which I saw in Montreal in the spring and was one of the big hits of the festival, and the best I could from anyone was, "I like Serge Gainsbourg." There isn't even that much music in the film, but maybe if I were a bigger fan of Gainsbourg's work, I'd be more interested in all the broads he schtupped between the Occupation of Paris and the mid-1980s. (The film ends just before L'Affaire Whitney Houston, maybe because she wouldn't schtup him--but then, why bother recreating something you can watch on YouTube?)

But I digress... Now, I don't want to skull-fuck a dead cat or nothing, but Man of a Thousand Songs is a rather unambitious documentary about Newfoundland singer-songwriter Ron Hynes that alternates between talking head interviews with Hynes and his nephew, and the former performing various gigs around the province. What the film lacks is a sense of urgency. The whole point of making a documentary is that you're filming an event that's unrepeatable, whether it's the Beatles' first US tour or Dave Chappelle's block party. So why is Magillvray making this film now? More importantly, the film lacks a structure, so even though it's not a long movie (ninety minutes), it just seems to go on and on and on. And without any attempt to place Hynes' music in a broader historical context, what we're left with is a walking cliché: The hard-living singer-songwriter whose early commercial success came to little, wrestling with his personal demons (i.e., cocaine). Didn't Jeff Bridges like just win an Oscar for playing exactly the same character?

Sunday, September 26, 2010

AFF #4: Some Are Born to Endless Night

It's a funny thing about festivals: Watch any random sampling of movies in a concentrated period of time, and eventually a theme will begin to emerge. And the major theme of the thirtieth Atlantic Film Festival (at least in my experience) was death. The best film I saw by a rather wide margin was Apichatpong Weerasethakul's mystical Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) about a man dying of kidney failure in a Thai farmhouse. There, he's visited by spirits, recalls his past lives as an ox and a princess, and describes a vision he had of the future. Joe said in an interview in Cinema-Scope that he still believes in reincarnation, but that he has doubts and would like to see more scientific evidence. The film's ending suggests that we not only live again and again, but that we live multiple lives simultaneously.

I was also impressed by Woody Allen's atheistic You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010), a multi-protagonist comedy-drama set in London that only seems to be about romance, but ends in an unexpected way that makes you realize that the real subject of the film, lurking just behind the merriment, is death. I left the theatre feeling profoundly satisfied, making this the festival's most unlikely feel good movie. And then there was Yael Hersonsky's powerful documentary A Film Unfinished (2010) about the making of a Nazi propaganda film in the Warsaw Ghetto in the Spring of 1942--not to mention Javier Fuentes-Léon's disappointing Undertow (2009), a magic realist coming out story set in a Peruvian fishing village that suggested a cross between Brokeback Mountain (2005) and Ghost (1990).

To this inventory, I have two more films to add. First, Mike Leigh's Another Year (2010) is about a woman growing old alone. The plot is about a year in the lives of a happily married couple named Tom (Jim Broadbent) and Gerri (Ruth Sheen), and Gerri's unhappily single coworker, Mary (Lesley Manville), and as the seasons change, so does the film's colour scheme, reflecting the emotional tenor of the movie as it moves from a sad, blue spring to a cheerful, green summer, followed by a tense, brown autumn, and finally a winter that's sombre and black. I felt that the film peaked with the third segment, and after that, since there's really nothing left to say about how miserable and sad and pathetic Mary is, the story seems to be spinning its wheels. Leigh's mastery is evident throughout (a seemingly offhand remark turns out several reels later to be an ingeniously subtle bit of foreshadowing), but overall this strikes me as the least of his films since Career Girls (1997).

As in Happy-Go-Lucky (2008), Leigh's major insight here is that some people seem to have a natural gift for happiness which others simply lack. Leigh's most memorable characters are often the unhappiest--David Thewlis' existential drifter in Naked (1993), Brenda Blethyn and Timothy Spall as estranged siblings in Secrets & Lies (1996), the deranged driving instructor (Eddie Marsan) in Happy-Go-Lucky--and here Manville steals the show as a lonely woman heading into middle-age who drinks too much (even for a movie about British people, there's a lot of drinking in this film) and has a pathetic crush on Tom and Gerri's grown son, Joe (Oliver Maltman). I was hoping for a bit of spring at the end of the film's long, grim winter, but Leigh just fades to black on a note of despair, which I found unsatisfying. At one point in the film, Ken (Peter Wight), an old friend of Tom's who's even more of a loser than Mary, sports a t-shirt reading, "Less Thinking, More Drinking." And after a year with these characters, I felt like having a stiff drink myself.

The Dead Weight of a Quarrel Hangs

Incendies (2010)--Denis Villeneuve's ambitious new film about the civil war in Lebanon, adapted from a play by Wajdi Mouawad--is a kind of unofficial companion piece to Villeneuve's earlier Polytechnique (2009), another story about massacres and motherhood. (That film was a dramatization of the 1989 shooting at the École Polytechnique in Montreal.) After the haunting opening sequence of child soldiers having their heads shaved, scored to Radiohead's "You and Whose Army?," the story moves to Montreal where adult siblings, Jeanne (Mélissa Désormeaux) and Simon Marwan (Maxim Gaudette), go to their lawyer's office for the reading of their mother's will. In the will, their mother, Narwal (Lubna Azabal), stipulates that Jeanne and Simon must deliver two letters--one to the father they never met; the other to a half-brother they didn't know existed--before they can place a tombstone on her grave. As Jeanne and Simon discover more about who Narwal was, there are flashbacks to her early life in Lebanon. As a young woman, we learn, Narwal fell in love with a Muslim refugee from Palestine, which was a disgrace to her Christian family. After giving birth to a son, Narwal was sent to live with an uncle in a city to the north, and the child was placed in an orphanage. (Importantly, Narwal's mother tattooed three dots on the baby's heel so that Narwal would be able to recognize him.) Several years later, when the war breaks out between Christians and Muslims, Narwal returns to the south in search of her son, and there she witnesses atrocities at the hands of Christian nationalists that radicalize her, leading her to fight on the side of the Muslims.

I'll leave you to discover subsequent revelations for yourself, except to say that I found the ending a little too dramatically perfect. Obviously all stories depend on coincidence to some degree, but here, the Big Reveal felt contrived in order to make the point that Villeneuve (and presumably Mouawad) wanted to make about this conflict. And while this is clearly the most ambitious feature that Villeneuve (a native of Trois-Rivières based in Montreal) has ever attempted, in terms of its overall narrative structure (which is essentially that of a procedural, not so very different from The Secret in Their Eyes [2009]), it's also his most conventional with Best Foreign Language Oscar written all over it. In Polytechnique and now this film, Villenueve seems to find it inconceivable that he might somehow reconcile the flair for the fantastic that characterized his exciting early features Un 32 août sur terre (1998) and Maelström (2000) with his ambition to grapple with serious issues in his later work. Consequently, he's become precisely what I used to admire him for not being: another square, middlebrow Canadian director like Thom Fitzgerald or Sarah Polley.

La Nuit américaine

Two other themes of this year's Atlantic Film Festival were nighttime photography (I still contend that Uncle Boonmee has the best I've ever seen, in any of my past lives) and stories about young lovers. On the latter count, the best film I saw was obviously Xavier Dolan's Les Amours imaginaires (still the Québécois film to beat for 2010) for its Wong Kar-wai inspired slow motion shots of the two leads walking down Montreal streets, memorably set to Dalida's "Bang Bang," and because Dolan seems to get that these people are idiots, making this one of the funniest films of the festival. (Its treatment of imaginary loves is, in any event, a lot more enjoyable and less depressing than Another Year's.) I was also charmed by Ingrid Veninger's Modra (which I would hope is not the best English Canadian feature of 2010) about a pair of cute kids from Toronto who have a mostly cute time together in Slovakia, which I liked mainly for the beguiling lead performances by Hallie Switzer and Alexander Gammal.

I was less keen on David Robert Mitchell's The Myth of the American Sleepover (2010), even though next to Modra it's obviously more accomplished as storytelling and more ambitious (but not that ambitious), crisscrossing between several plot lines that unfold over a twenty-four hour period--a structure that inevitably invites comparisons with Richard Linklater's Dazed and Confused (1993). However, I wasn't sure if the film wanted me to feel nostalgic for my lost days of youth (in which case it failed because the kids don't do anything very exciting that would make me think, "Oh man, I was I were a teenager again"--quite the opposite, in fact), or whether it wanted to show things as they really are (in which case it's authentic but just not particularly interesting). I wanted either the film to be lighter and snappier, or better still, darker and angrier. As it is, it's enjoyable but slight.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

AFF #3: A Woody Allen Classic

You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010) is one of Woody Allen's best and most fully realized recent pictures, a multi-protagonist romantic drama set in London that paradoxically handles a serious subject with a light touch. The film begins with Helena (Gemma Jones), an elegant middle-aged woman going to see a fortune teller, Cristal (Pauline Collins), as we come to learn, because she was so devastated when her husband, Alfie (Anthony Hopkins), left her that she had a nervous breakdown and attempted suicide. Going to the fortune teller gives Helena some measure of comfort, so her daughter, Sally (Naomi Watts), indulges her illusions, but Sally's American husband, Roy (Josh Brolin), a struggling writer with a background in medicine, doesn't like it one bit--especially when Cristal predicts that Roy's publisher will reject his latest book.

I was surprised at first that the film ended where it does, because it doesn't wrap everything up very neatly, but then, as I thought back on it, I realized what Allen was up to, and it actually changed in retrospect my whole understanding of what the film was about. This is a film that works through misdirection, so that the real subject of the movie sneaks up on you, even though it's right there in front of you the whole time. It only seems to be about romance--Helena's new relationship with a widower, Jonathan (Roger Ashton-Griffiths), who shares her spiritual outlook; Alfie's sudden decision to marry a prostitute, Charmaine (Lucy Punch); Sally's crush on her new boss, Greg (Antonio Banderas); and Roy's infatuation with the South Asian girl next door, Dia (Freida Pinto). But the film is really about the certainty of death, and how people try to deal with that fact by having children, making art and literature, believing in an after life or reincarnation. And yet, even though it's a movie about death, and even though what happens to the characters is pretty harsh, as I left the theatre I felt an incredible sense of satisfaction, having seen a film that is so thoroughly entertaining and so cleverly written. This is Woody Allen at the very top of his form.

Les Amants canadienne

The first thing one notices about Xavier Dolan's Les Amours imaginaires (2010) in relation to his earlier J'ai tué ma mère (2009) is that, on this film, he had considerably more money at his disposal. And the characters in this movie--a stylish, funny, beautifully color-coordinated comedy about a trio of Montreal hipsters--are accordingly a good deal more affluent, even though none of them appears to have a job. (One gets an allowance from his mother; and though the other two have frequent sexual encounters with various strangers, we never see any money changing hands, so it's possible they're just sluts.) For better or for worse, Dolan establishes himself here as Canada's answer to Sofia Coppola, and the real significance of the film's epilogue, in which Louis Garrel makes a brief cameo, and which brings the narrative full circle, is that it extends Dolan's cool beyond Quebec's borders, putting him on the same plane as Christophe Honoré, another Nouvelle Vague-inspired movie brat (one who, incidentally, owes his entire career to Garrel).

Perhaps the most impressive thing about the film--in which best pals Francis (Dolan) and Marie (Monia Chokri) vie for the affections of Nico (Neils Schneider), while outwardly pretending to be uninterested--is how much comic mileage it gets out of such a threadbare scenario. There's a fine line between knowingly making a film about vapid characters and simply making a vapid movie (for instance, I disliked Coppola's Lost in Translation when I saw it at the film festival in 2003, but I loved Marie Antoinette [2006] enough to put it on my list of the decade's best movies), but I'm pretty sure that Dolan knows that these people are idiots. And as we know from J'ai tué ma mère, he's not particularly concerned with playing characters that are likable. However, although the film's central ménage à trois is calculated to remind us of Nouvelle Vague landmarks like François Truffaut's Jules et Jim (1962) and Jean-Luc Godard's Bande à part (1964) (Chokri has a face like Jeanne Moreau and hair like Anna Karina), the story lacks the serious undercurrents of those films.

J'ai tué ma mère established Dolan as an eclectic stylist, apparently willing to try anything once, and though that eclecticism is still apparent here, Les Amours imaginaires is a much more deliberate film. It feels like the work of a director who knows what he wants to do and how to do it, rather than a novice still feeling his way around. Again there are direct-address confessionals, but this time Dolan doesn't embed them within the narrative as a video journal, or bother with the redundancy of filming these scenes in black and white in order to distinguish them from the movie's dramatic scenes. Also, there are several speakers instead of one, and none of these characters appear in the narrative proper. And again Dolan employs slow motion like it was going out of style, and his debt to Wong Kar-wai is even more apparent here when he films Francis and Marie walking to various dates with Nico in slow motion, scored to Dalida's "Bang Bang." What's new is Dolan's frequent recourse to a more handheld style of shooting (rather than the sustained static two-shots of his debut), and a fantasy insert of marshmallows raining down on Nico (but then, it may be the case that there were similar scenes in J'ai tué ma mère that I'm forgetting). This is one scary talented kid.

The Kids Are Pretty Cute

Speaking of kids, Ingrid Veninger's low-budget Canadian feature Modra (2010) is a cute movie about a pair of cute kids from Toronto who spend a mostly cute time together in Slovakia, which is evidently so safe that they can sleep outdoors on a public bench without anyone harvesting their organs (as would surely happen on any street in Canada). As the film opens, Lina (Hallie Switzer), a seventeen-year-old girl, decides to take Leco (Alexander Gammal), a boy she barely knows, with her to Slovakia when Lina's boyfriend suddenly breaks up with her the day before her flight. ("Have fun in Slovenia." "It's Slovakia, ass-hole!") At times, the film suggests a children's-strength version of Billy Wilder's Avanti! (1972), but with fewer plot contrivances. It's not particularly ambitious or original, but after a somewhat heavy weekend (A Film Unfinished, The Illusionist), I was in the mood for something light and beguiling, and on that level, Modra delivered.

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

AFF #2: Fakin' It!

The Holocaust is different from other genocides in that there exists so much footage of it. How many people remember the Herero genocide, other than those who've read Thomas Pynchon's V. (1963) and Gravity's Rainbow (1973)? This time, the Germans kept meticulous records and made films because they wanted people to know what they were doing. Perhaps significantly, the best and most comprehensive film I've seen on the Holocaust, Claude Lanzmann's Shoah (1985), doesn't incorporate any archival footage whatsoever.

The approach taken by Yael Hersonsky in his powerful documentary A Film Unfinished (2010) is directly the opposite of Lanzmann's in that it focuses like a laser on one particular event: The making of a Nazi propaganda film in the Warsaw Ghetto in the spring of 1942. Four reels of edited footage, running about an hour, were discovered in an underground film vault in Eastern Germany after the war, but why the film was made, why it was never completed, and the names of all but one of the technicians who worked on the film remain a mystery to this day. The documentary consists primarily of the surviving footage, including outtakes that show the same events being staged over and over from several different angles. The footage, which lacks a soundtrack, is contextualized by the reminiscences of Holocaust survivors watching the film in a screening room, as well as excerpts from the diary of Adam Czerniaków, the head of the Jewish Council in the Ghetto, who wrote daily about the making of the film (his diaries are also featured prominently in the latter portions of Shoah), and from the testimony given by Willy Wist, a cameraman who worked on the film, during the trial of a German officer.

The film, titled simply The Ghetto, attempts to present a comprehensive view of life in the Warsaw Ghetto, including ritual baths and circumcisions, with a particular emphasis on the supposed disparity between the rich and the poor, and the indifference of more affluent Jews to those dying in abject squalor. One survivor of the Ghetto estimates that there were between twenty and fifty people who could afford to buy food right until the end (at exorbitant prices), but the scenes in the film of rich, healthy-looking Jews thriving and enjoying their lives were obviously staged for the camera. But what were they trying to prove? Apparently, the filmmakers themselves didn't know; they filmed what they were told to film. My guess is that the film was intended as a rationalization for the liquidation of the Ghetto, which occurred shortly afterward, but when it wasn't finished on time for whatever reason, the film was simply abandoned. As a record of how the Nazis wanted the world to see the Warsaw Ghetto, A Film Unfinished is a fascinating historical document.

Hasid Streets

A Rabbinical school version of Scarface (1983), Kevin Asch's Holy Rollers (2010) takes place in a black-and-white universe in which everything the characters do is either a step towards Hashem, or a step away. As the film opens, its protagonist, Sam Gold (Jesse Eisenberg), is an ultra-Orthodox George Michael (you better believe he's gotta have faith-a-faith-a-faith... Baby!) whose parents want him to become a Rabbi. Sam, however, wants to continue working in his father's fabric store so that he can make some extra money to buy his ma a new oven, and support the girl he intends to marry, who comes from a more affluent family. Leon (Jason Fuchs), Sam's best friend, is also studying to be a Rabbi, but his older bother, Yosef (Justin Bartha), watches porn, smokes on the sabbath, and wears a gold watch. It's through Yosef that Sam meets Jackie (Danny Abeckaser), an Israeli drug dealer who imports ecstasy pills from Amsterdam using Hasidic Jews as drug couriers.

Jackie introduces Sam to a life of fast money and fast women, not to mention flashier clothing. But temptation begets temptation, and before long, Yosef is skimming drugs off the top to sell on the side, and Sam enters into an Oedipal struggle with Jackie over the latter's girl, Rachel (Ari Graynor), a blonde temptress whose first step away from Hashem was to drop out of Hebrew school. Throughout it all, Sam remains fundamentally a nice kid. When trying to convince Rachel to run away with him to Lithuania (where they'll live with his grandmother!), Sam tells her, "I think we make a cute couple." On the other hand, Leon stays on the righteous path and marries the girl that Sam wanted to, while Sam, Yosef, Jackie, and Rachel all go to prison. A bit neat, don't you think? The film's message is essentially that you should just do whatever your parents tell you to do.

The film is very well made. I liked the style of the film (shadowy handheld realism with virtually no non-diegetic music), and Asch has a good handle on the tone of the material. And I liked Eisenberg, who's more of a leading man than Michael Cera. In short, it's probably the best after school special ever made. But to cite the last mainstream Jew-fest to hit the 'plexes, I was much more intrigued by the Coen brothers' A Serious Man (2009), which is all about uncertainty and doubt. (Incidentally, both films use selective focus to represent an altered state of mind.) This movie, on the other hand, for all its claims to taking place in the secular world, never seems to leave Rabbinical school.

Down by Law

Cameron Yates' The Canal Street Madam (2010) is a documentary profile of Jeanette Maier, a self-described "whore" from New Orleans whose arrest in the late 1980s attracted national media coverage and inspired a made-for-TV movie starring Annabella Sciorra. Yates began filming Maier in 2004 and followed her over a period of several years, and the resulting documentary suggests at different times a political activism doc, with Maier campaigning to have prostitution decriminalized; a feminist statement about how Maier has been exploited by men; and a reality show train wreck in which Maier (unwittingly?) makes a fool of herself on camera.

It's not so much that Yates portrays Maier in an unflattering light so much as that's how she portrays herself. After being interviewed by the local six o'clock news, Maier gets into an argument with her boyfriend, who thinks that she should be more careful about the language she uses to represent herself--for instance, instead of saying "whore," he thinks she should use the more politically correct "prostitute." Maier answers, not unreasonably, that "a whore is a whore is a whore" no matter what you call her. And her best friend thinks it's okay to say "whore" if you are one. All valid points of view. But surely it doesn't help Maier's cause to decriminalize prostitution when, while campaigning for local office, she stands on a street corner holding up a sign while giggling her boobs at passing motorists.

Let's agree that the prostitution laws in the United States are ineffective and hypocritical, targeting the prostitutes while protecting their clients. (The film touches on the dubious suicide of the DC Madam, Deborah Jeane Palfrey, after she decided to name names. And the undercover cop who busted Maier waited until after she sucked his dick before arresting her--or at least, that's how she tells it.) When you get down to it, the fact of the matter is that a woman with no education, no skills, no legitimate work experience, a criminal record, and three kids to feed can make a hell of a lot more money selling her ass than she can working at Denny's for minimum wage and tips. It's easy money, like teaching English abroad--except that you don't need a university degree to do it, and you don't pay taxes. (After her arrest, however, Maier started another business, selling candles for three hundred dollars a pop, and whatever she does with a customer afterward is simply for her own pleasure.)

Not surprisingly, all of Maier's children have criminal records. Her eldest son is an intravenous drug user; her daughter also became a prostitute; and her youngest son spent time in prison for an unspecified offense and now lives at home with his mother. Maier attributes her kids' problems to their having seen her being abused by the cops from the time that they were children, but this is obviously a self-serving rationalization so that she doesn't have to take any responsibility for her actions. My theory is that kids learn by example, and if they see a parent engaged in illegal activity, they're going to think it's okay. Do I need to tell you that Maier's mother was herself a lady of the evening? (Ellen Burstyn played her in the TV movie.)

Aside from infrequently asking a question while standing off screen, Yates mostly keeps himself out of the picture, letting Maier speak for herself. Watching the movie, I had the same queasy feeling that I got from Chris Smith's American Movie (1999), in which you sense that the people on screen aren't in on the joke. The curious thing about the movie is that Yates isn't pretending to be objective; rather, he seems to be giving Maier a platform to espouse her views. So when he includes footage showing her and members of her family in an unflattering light, I felt that he wasn't being entirely upfront about his intentions, either with Maier or the audience.